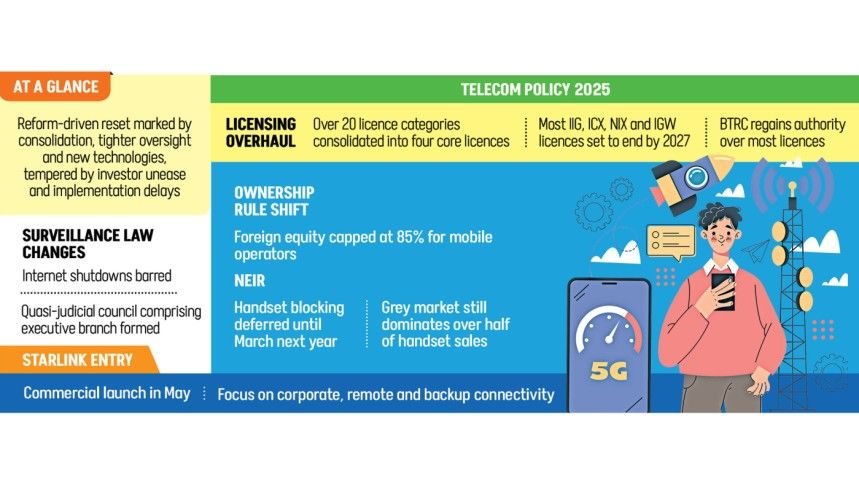

As 2025 comes to a close, Bangladesh’s telecommunications sector finds itself at a critical inflection point, reshaped by sweeping policy reforms that have redefined regulation, ownership structures, and governance. Over the year, the government overhauled telecom licensing, amended long-standing surveillance laws, fast-tracked satellite internet entry through Starlink, and revived efforts to block unauthorised handsets via the National Equipment Identity Register (NEIR).

Faiz Ahmad Taiyeb, special assistant to the chief adviser for telecom and ICT, said the reforms were necessary to address years of disorder in the sector, marked by politically driven licensing and rent-seeking intermediaries. While industry stakeholders largely agree that reform was overdue, concerns persist that several measures could weaken competition, deter investment, and reinforce the dominance of large multinational players.

At the centre of the reform agenda is the new Telecommunication Licensing Policy approved in September. It replaces more than 20 licence categories with four core types covering access networks, national infrastructure, international connectivity, and non-terrestrial networks, while shifting telecom-enabled services to a registration model. Existing licences will be allowed to expire by 2027. However, the policy has raised alarm over ownership rules, particularly a cap limiting foreign equity in mobile operators to 85 percent. This would require several operators to dilute foreign holdings, prompting warnings that forced local share offloads could unsettle long-term investors.

Industry leaders have also flagged inconsistencies that may disadvantage domestic firms, noting that multinational operators with high foreign direct investment can access cross-layer licences more easily than local companies. Critics argue that weak cross-ownership limits risk distorting competition and marginalising smaller domestic players.

Another major shift came with the Bangladesh Telecommunication (Amendment) Ordinance, 2025, which bans state-led internet shutdowns and introduces new safeguards around lawful interception. The ordinance establishes a quasi-judicial council to oversee interception requests, imposes penalties for misuse, and restores some regulatory authority to the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission. However, experts question whether the council’s executive-heavy composition can ensure genuine independence.

The NEIR initiative remains contentious. Intended to curb illegal handset imports in a market dominated by grey-channel sales, its enforcement has been repeatedly delayed following protests from small traders. Authorities have extended registration deadlines, with disconnections deferred until at least late March next year.

Starlink’s entry has further altered the landscape. The satellite internet provider received rapid approvals, launched services within months, and secured reseller agreements with local partners, introducing new competition in connectivity and expanding options for underserved areas.

Together, these developments mark a decisive policy reset for Bangladesh’s telecom sector. Yet unresolved tensions around ownership, regulatory balance, and market fairness suggest that while the framework has been rewritten, structural fault lines remain.